Writing Functions

Writing Functions

Docstrings

def count_letter(content, letter):

"""Count the number of times `letter` appears in `content`.

Args:

content (str): The string to search.

letter (str): The letter to search for.

Returns:

int

# Add a section detailing what errors might be raised

Raises:

ValueError: If `letter` is not a one-character string.

"""

if (not isinstance(letter, str)) or len(letter) != 1:

raise ValueError('`letter` must be a single character string.')

return len([char for char in content if char == letter])

如何直接获取

# Get the "count_letter" docstring by using an attribute of the function

docstring = count_letter.__doc__

border = '#' * 28

print('{}\n{}\n{}'.format(border, docstring, border))

<script.py> output:

############################

Count the number of times `letter` appears in `content`.

Args:

content (str): The string to search.

letter (str): The letter to search for.

Returns:

int

Raises:

ValueError: If `letter` is not a one-character string.

############################

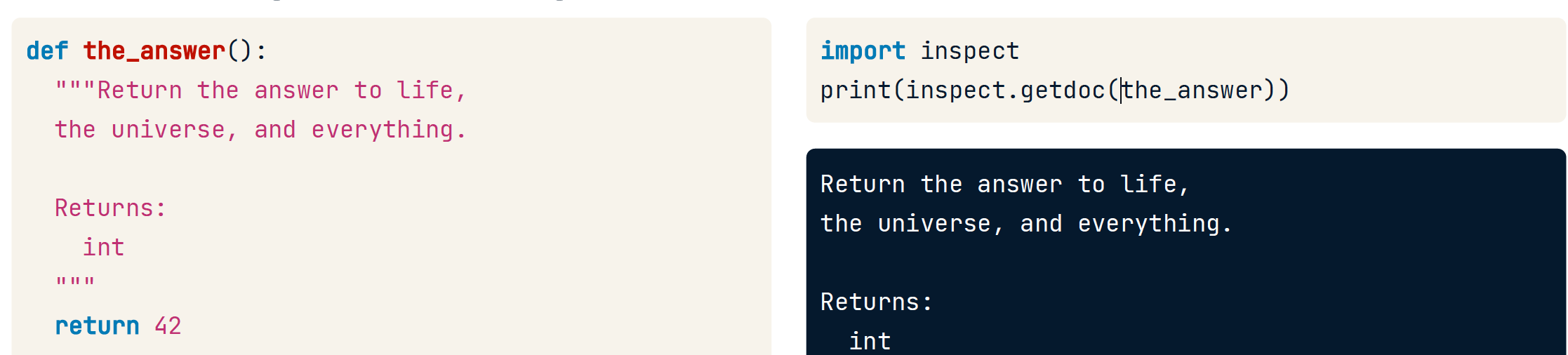

inspect.getdoc()获取

Pass by assignment

和Java 的 Pass by reference相似。只不过需要注意不能更改的变量有什么。

context managers

作用

- 设置一个上下文

- 运行你的代码

- 删除上下文

open()

open() does three things:

- Sets up a context by opening a file

- Lets you run any code you want on that file

- Removes the context by closing the file

Using a context manager

with <context-manager>(<args>) as <variable-name>:

# Run your code here

# This code is running "inside the context"

# This code runs after the context is removed

举例

with open('my_file.txt')as my_file: text = my_file.read() length = len(text)

print('The file is {} characters long'.format(length))

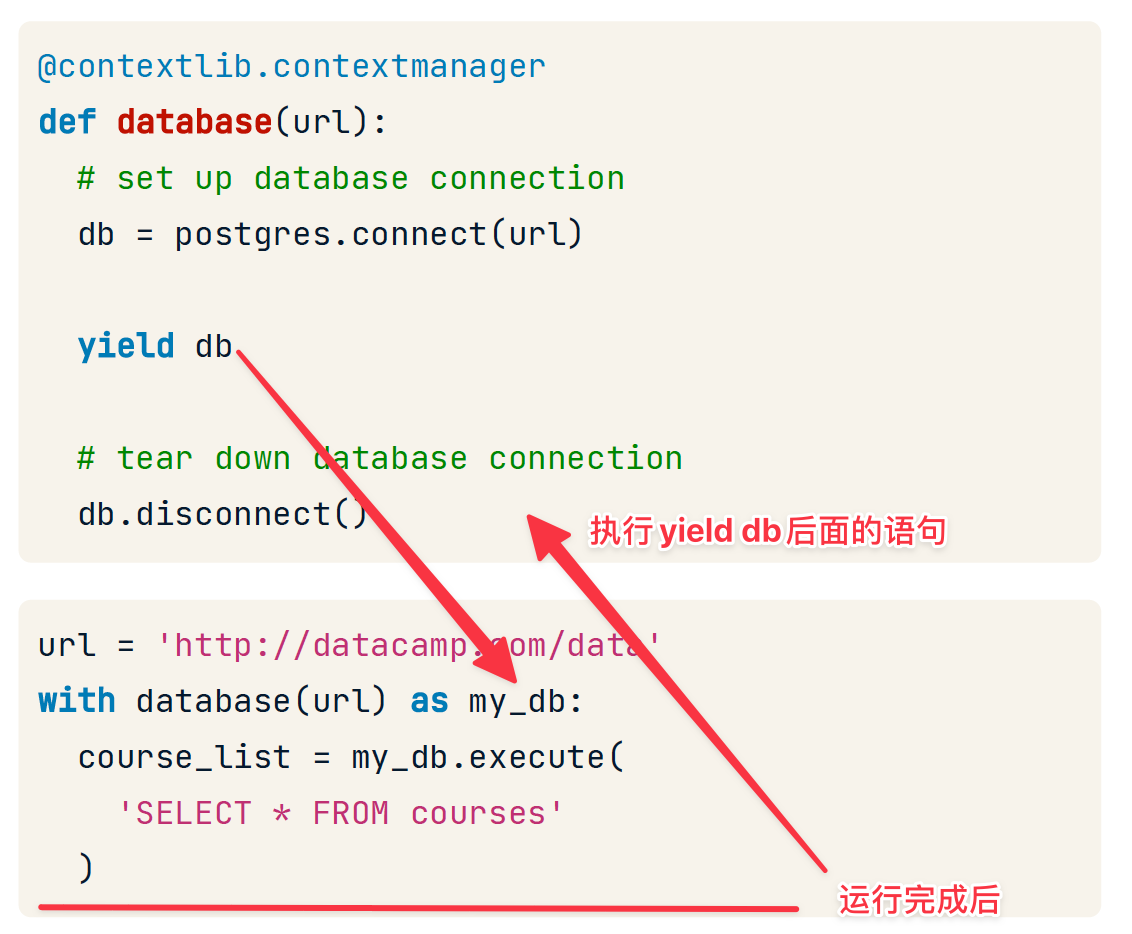

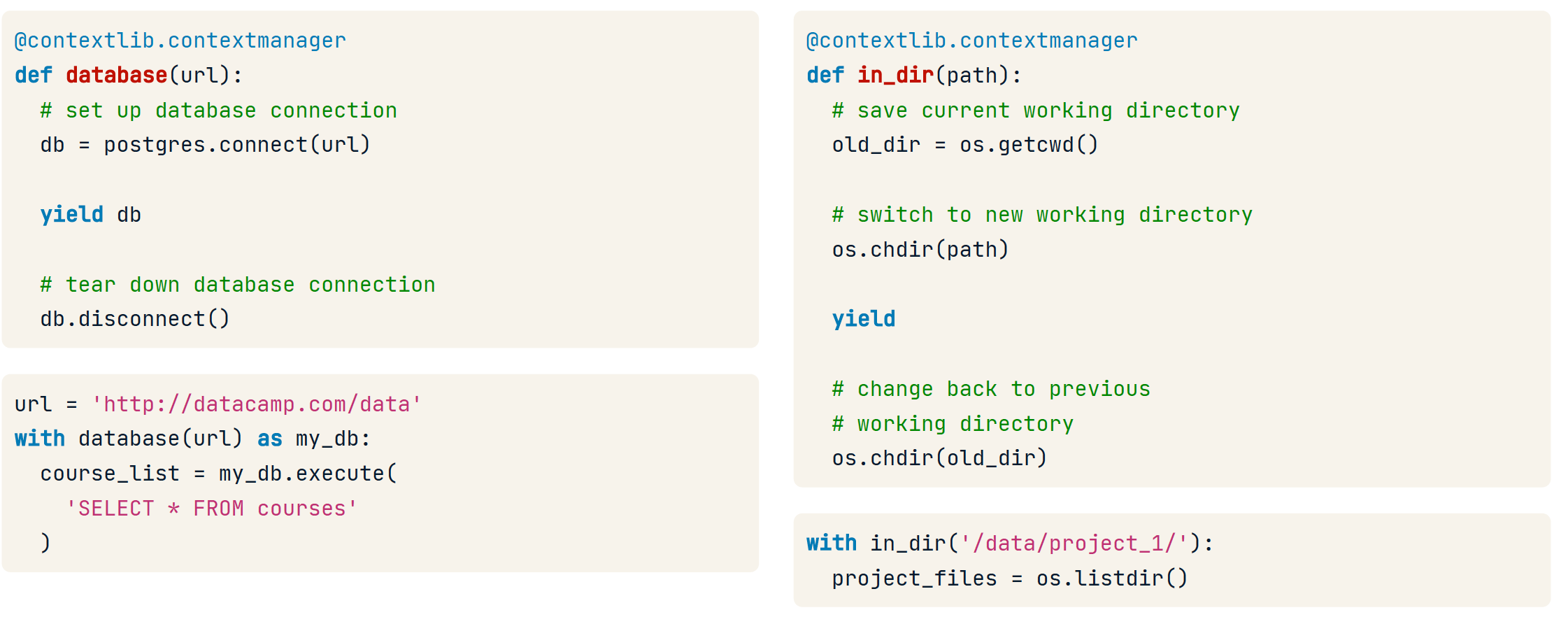

define a context manager

Two ways:

- Class-based

- Function-based

此处关注基于函数的

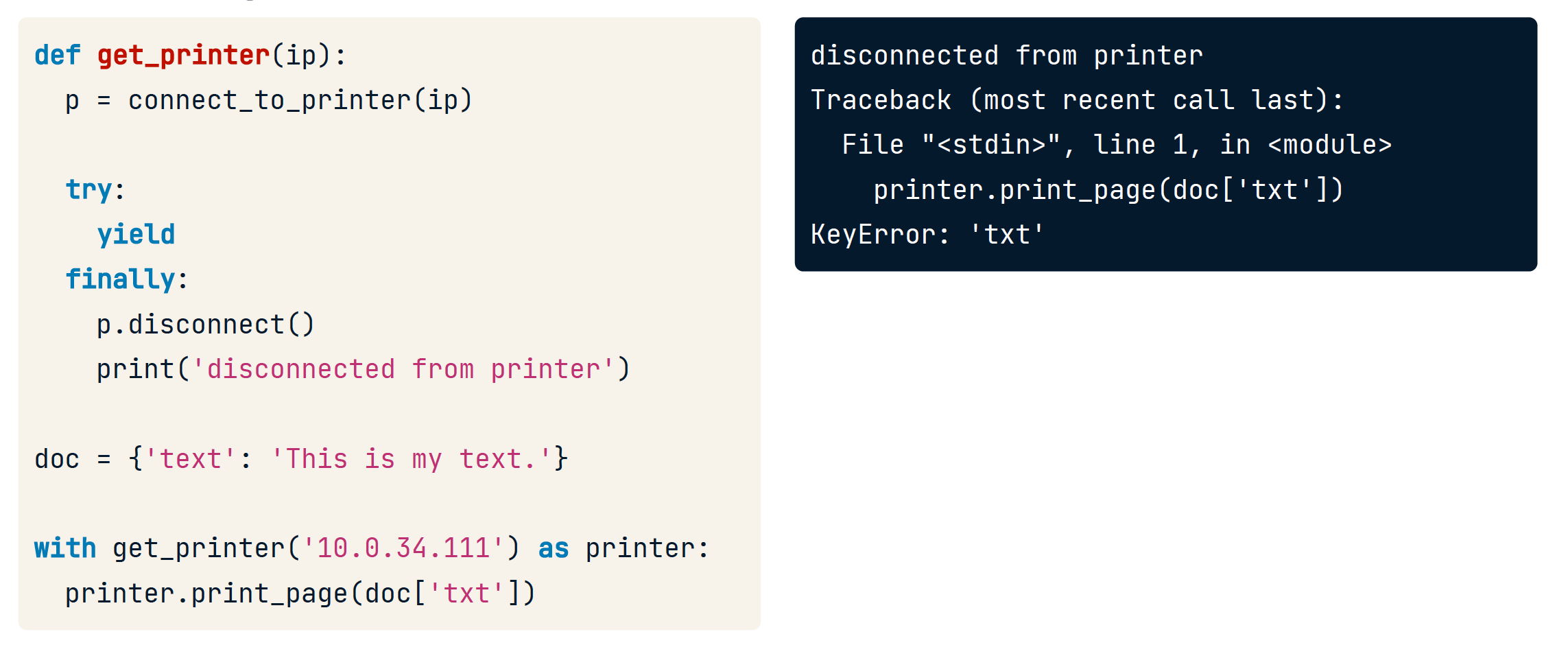

应当添加try-catch 保证最终一定关闭资源

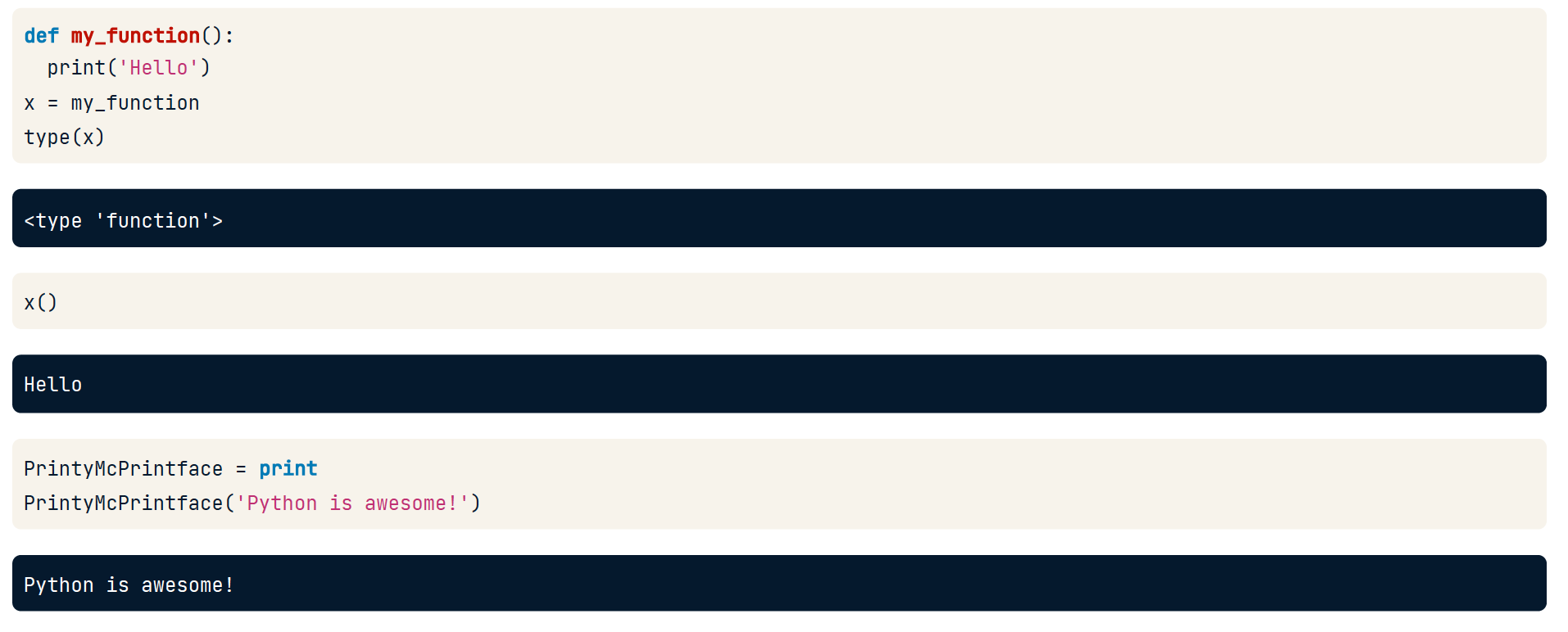

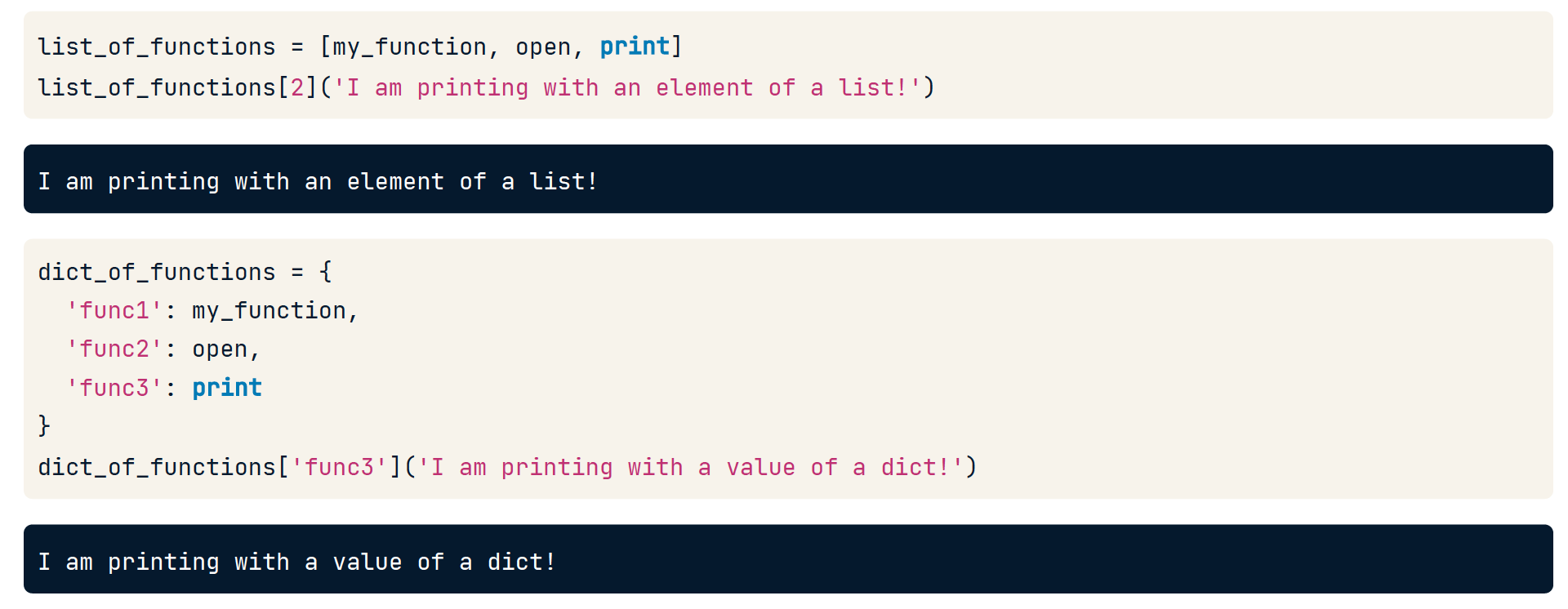

Functions as objects

Python 思想:一切都是 object

调用和赋值

Functions as variables

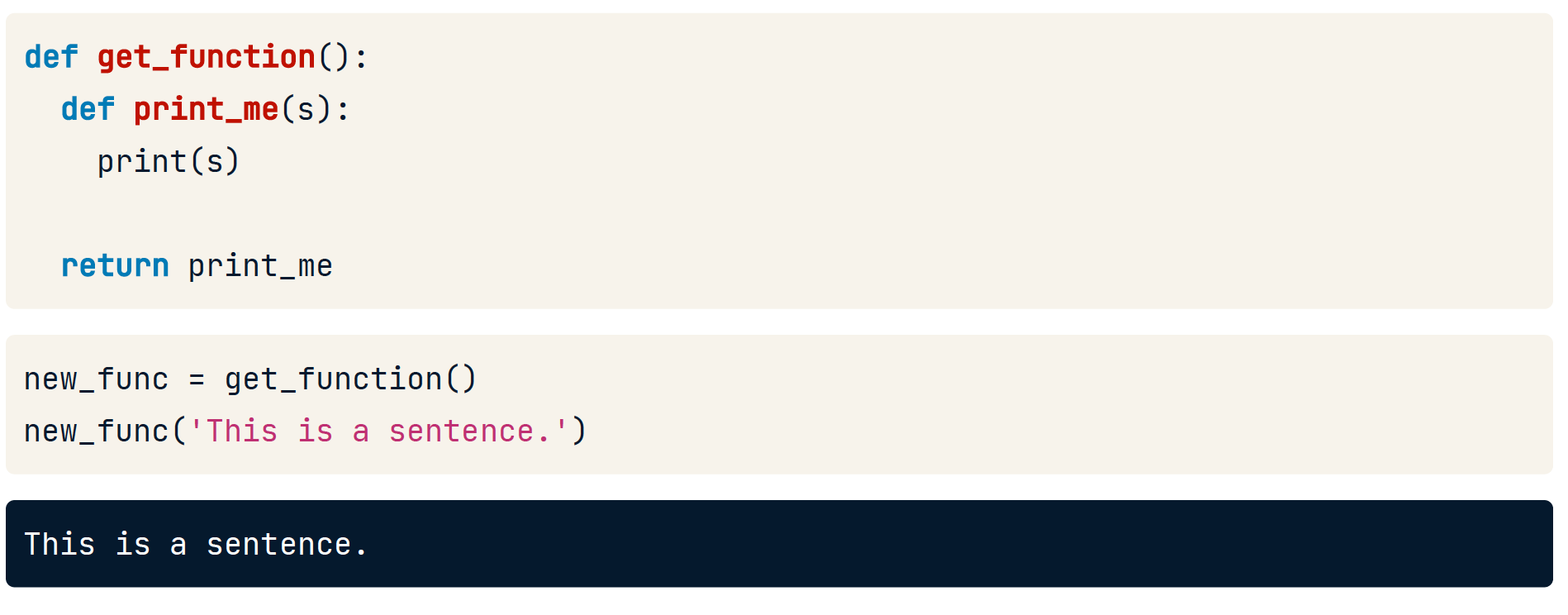

子函数

def foo():

x = [3, 6, 9]

def bar(y):

print(y)

for value in x:

bar(x)

同样的,子函数对象也可以作返回值

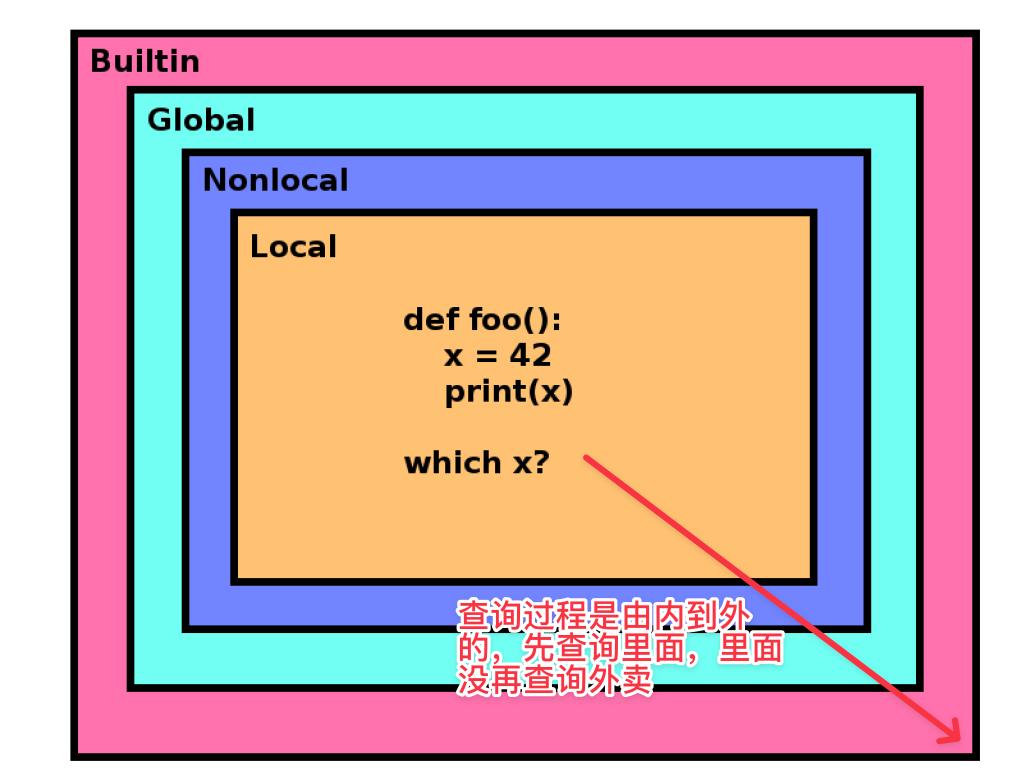

Scope

不妨先做个对比

| Language | 全局变量 | 局部变量 | 全局变量在函数内 |

|---|---|---|---|

| C/C++ | 有(函数外声明) | 有(函数/{}内声明) | 可读 可写 |

| Python3 | 有(函数外声明) (global函数内声明) | 有(函数内声明) | 可读, 不可写 加global后可写 |

| Java | 无(只有类变量,被成员共享访问) | 有(函数/{}内声明) | 类变量可读可写 除非用关键字控制 |

Python 变量作用域

全局变量在函数内可读不可写

x = 7

y = 200

def foo():

x = 42 #创建x为局部变量,忽略全局变量x

print(x)

print(y)

foo()

42

200

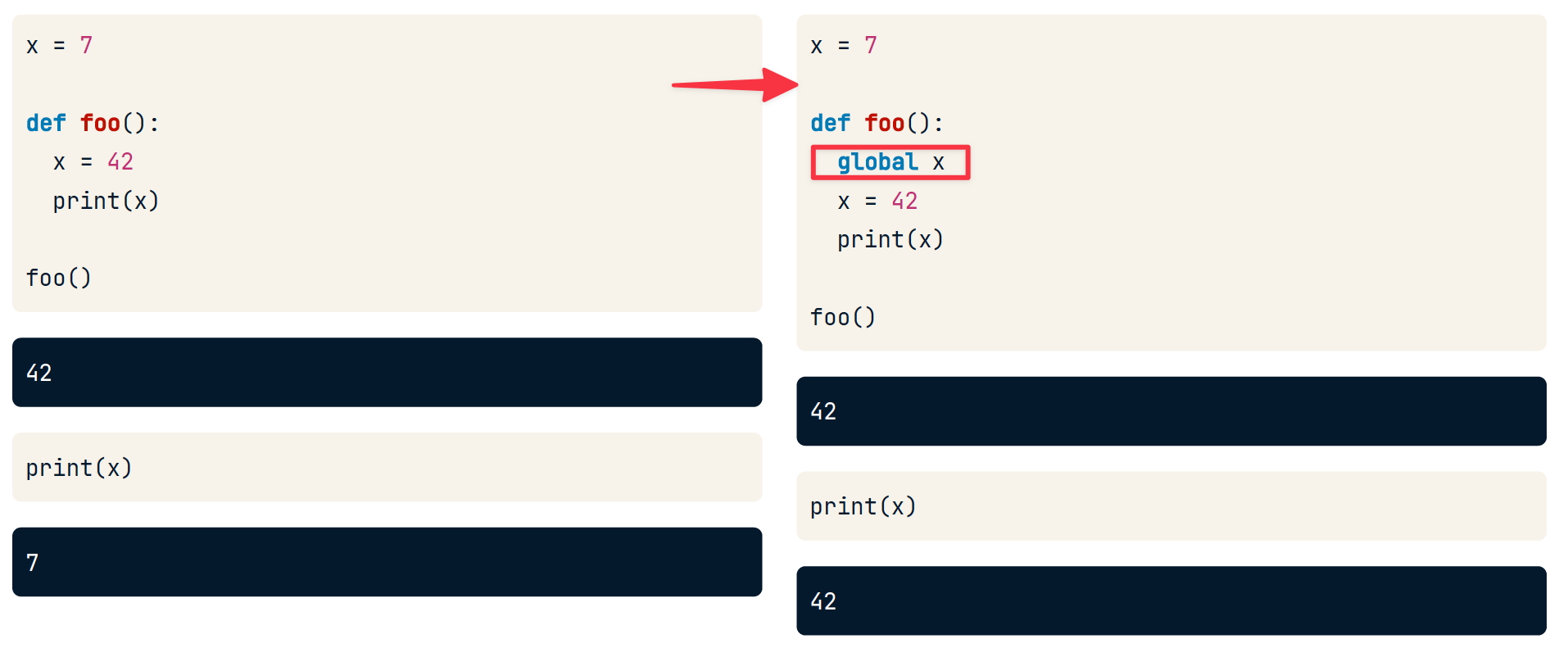

global 关键字

global 关键字在函数内修饰变量,有两个作用

- 在函数内声明一个新的全局变量,并且使该变量在函数内可读可写

- 若修饰的变量已经在全局定义,则使该变量在函数内可读可写

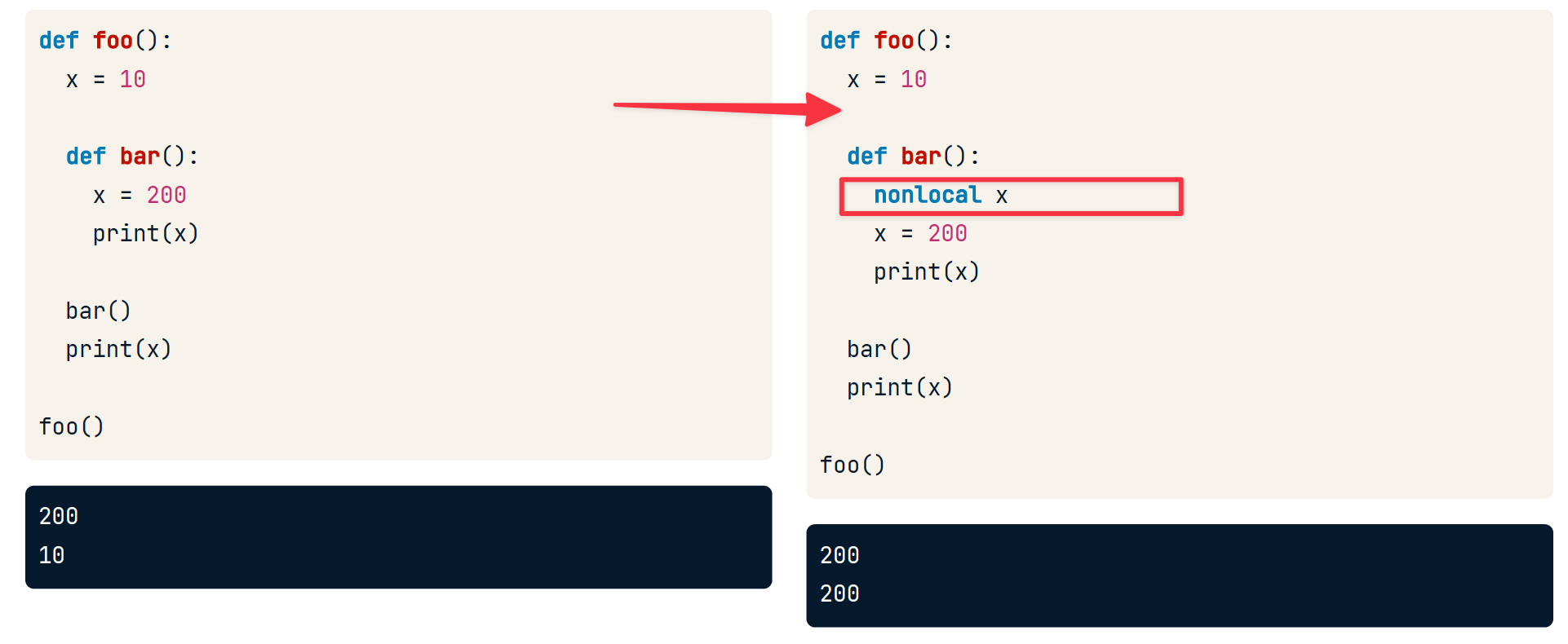

nonlocal 关键字

前面介绍了函数中可以创建子函数,然而子函数只能读取父函数的变量,并不能写。

nonlocal 关键字作用类似于global,是

在函数内声明一个新的变量,并且使该变量在其子函数内可读可写

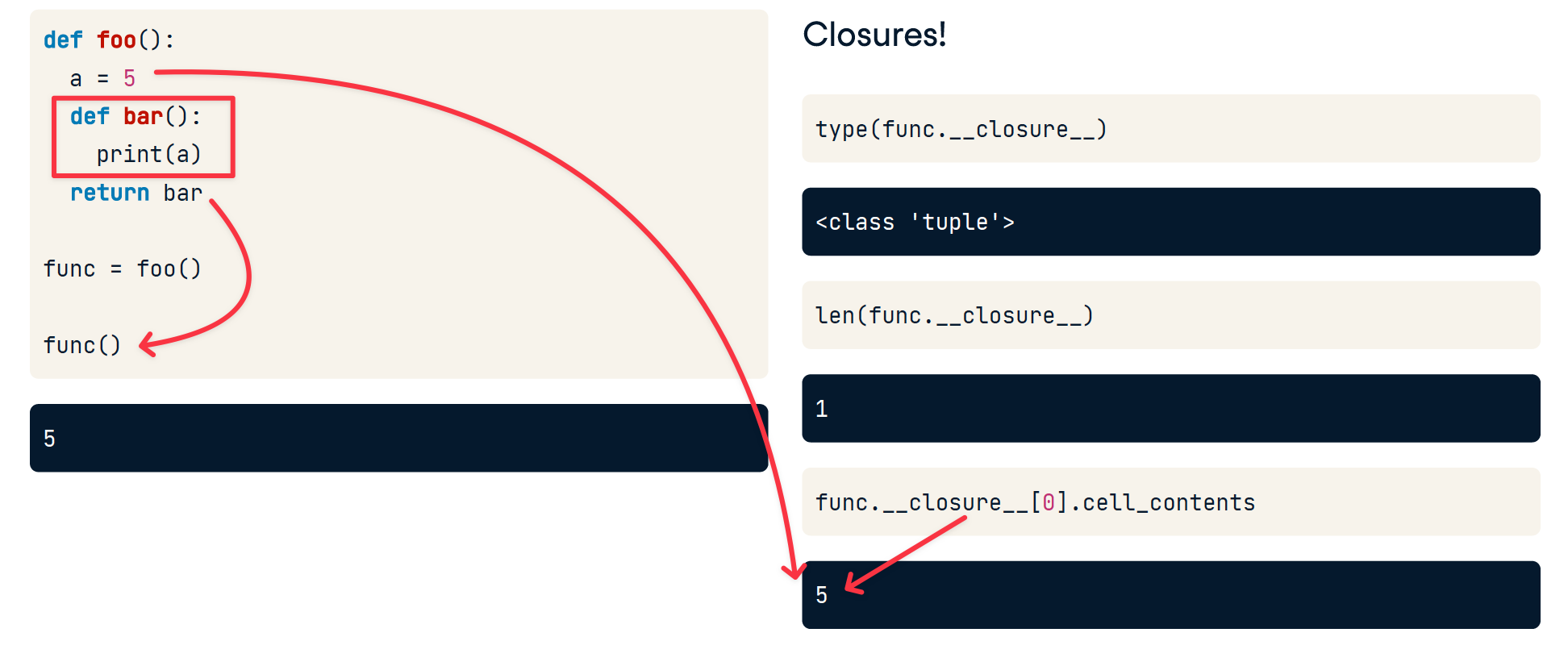

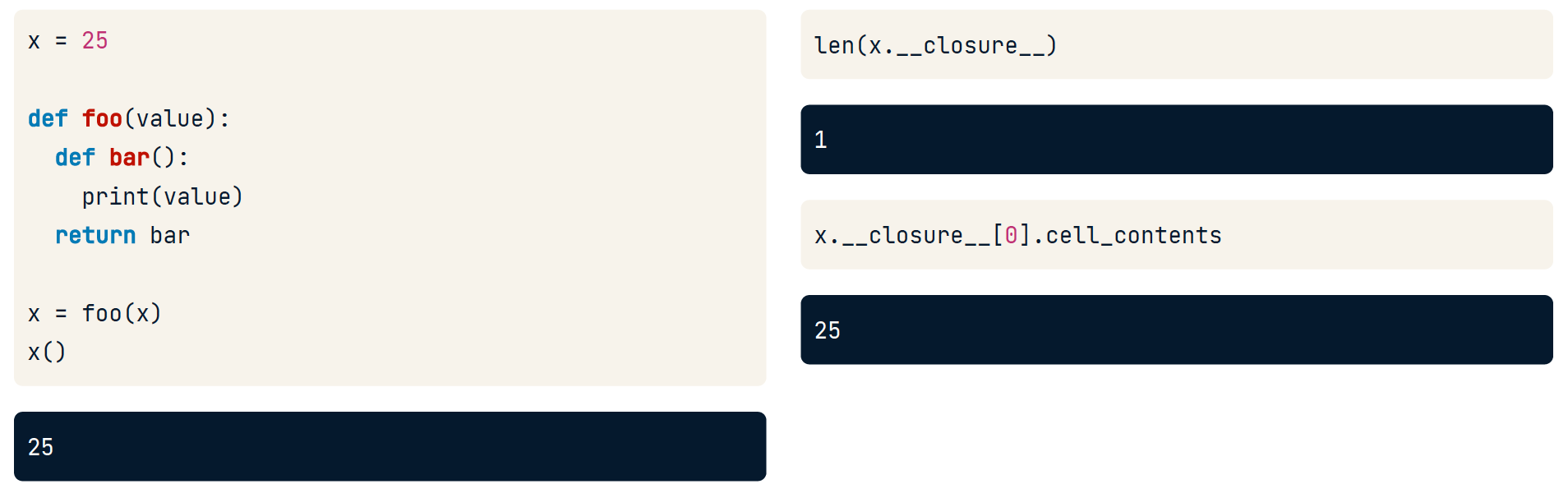

Closures

作用是 Attaching nonlocal variables to nested functions

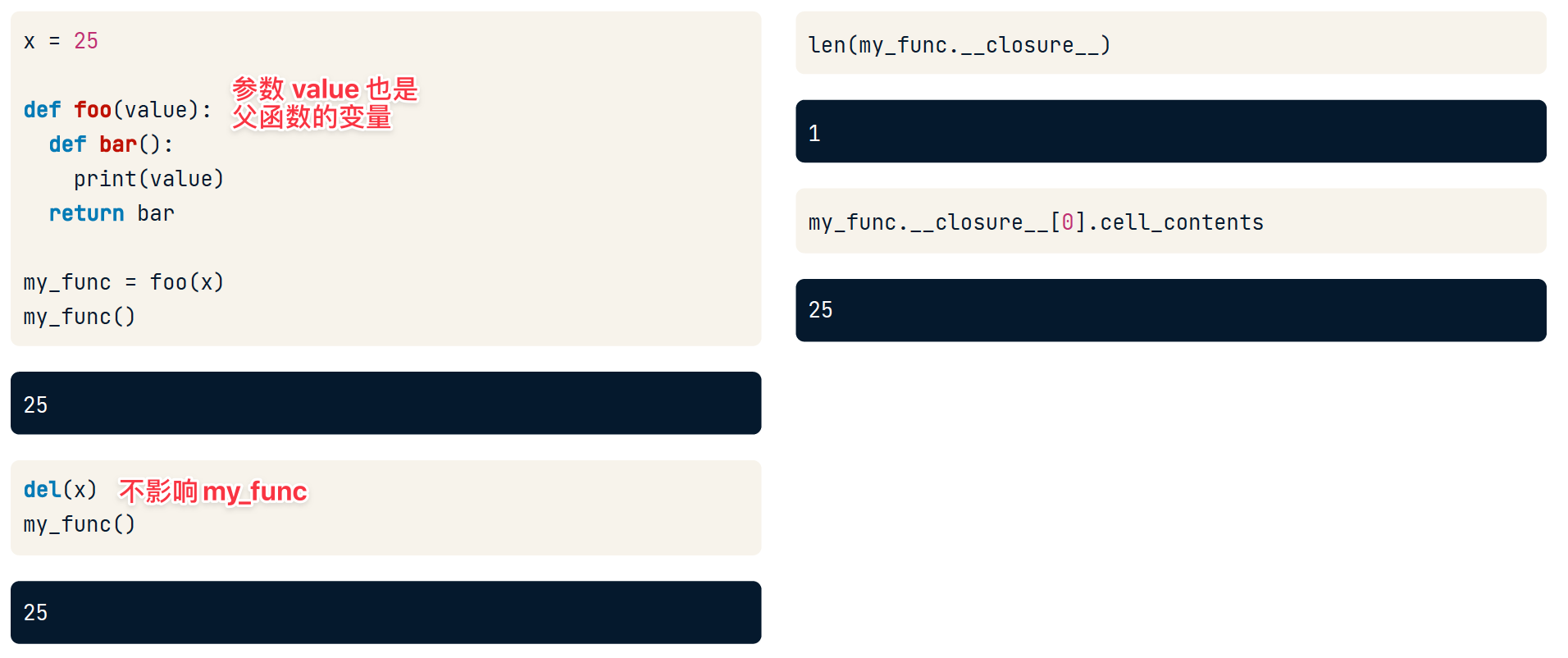

思考子函数 离开了父函数 被传递给一个新的引用后,子函数 需要的读的父函数变量怎么获取?

答案就是 传递时,会将函数需要的 父函数变量 复制一份,放到 返回的子函数的__closure__里面。

这里有一点需要注意的是每一次将返回一个新的子函数object,而不是共享一个子函数object

因此__closure__元组中的元素复制后就不会改变了。

删除变量不影响:

修改变量不影响:

Decorators

首先明确一点,Java注解(Annotation) 和 Python的装饰器(Decorators)不是一个东西。Java也有Decorators。

Decorators 的功能总的来说就是劫持函数并修改其功能,实质是用一个新的函数把旧的函数进行一些修改后包装起来。

- 修改输入

- 修改输出

- 改变函数本身的行为

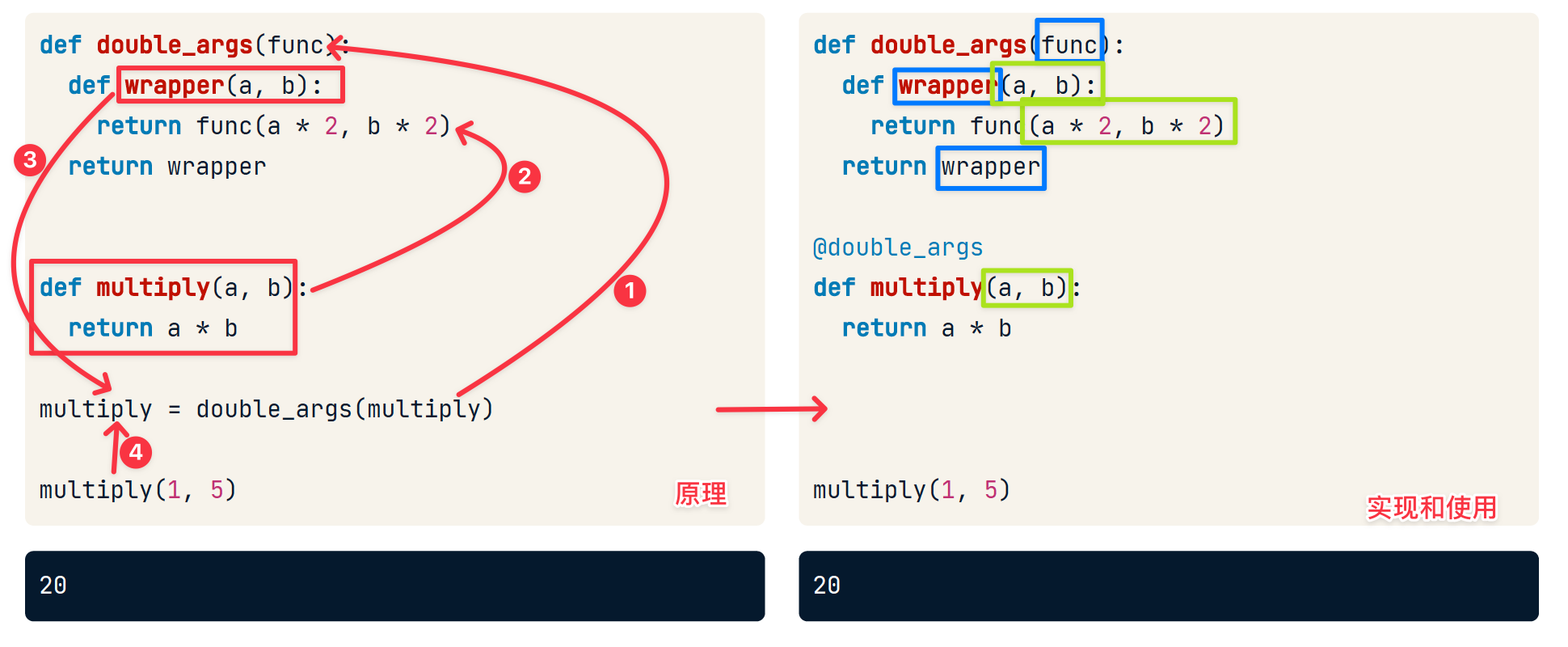

使用修饰器

@double_args

def multiply(a, b):

return a * b

multiply(1, 5)

20

创建修饰器

修饰器本身就是一个函数,以目标函数为参数,修改目标函数,之后把修改好的目标函数传传递给原引用。

在创建修饰器的时候,需要注意的是应把修饰器函数的

- 接受唯一参数,即函数object

- 返回唯一参数,即函数object

- 返回的函数object的 参数个数以及类型顺序 应当和旧函数的 参数个数以及类型顺序 相同。

示例1

def print_before_and_after(func):

def wrapper(*args):

print('Before {}'.format(func.__name__))

# Call the function being decorated with *args

func(*args)

print('After {}'.format(func.__name__))

# Return the nested function

return wrapper

@print_before_and_after

def multiply(a, b):

print(a * b)

multiply(5, 10)

Before multiply

50

After multiply

示例2

def counter(func):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

wrapper.count += 1

# Call the function being decorated and return the result

return func(*args, **kwargs)

wrapper.count = 0

# Return the new decorated function

return wrapper

# Decorate foo() with the counter() decorator

@counter

def foo():

print('calling foo()')

foo()

foo()

print('foo() was called {} times.'.format(foo.count))

calling foo()

calling foo()

foo() was called 2 times.

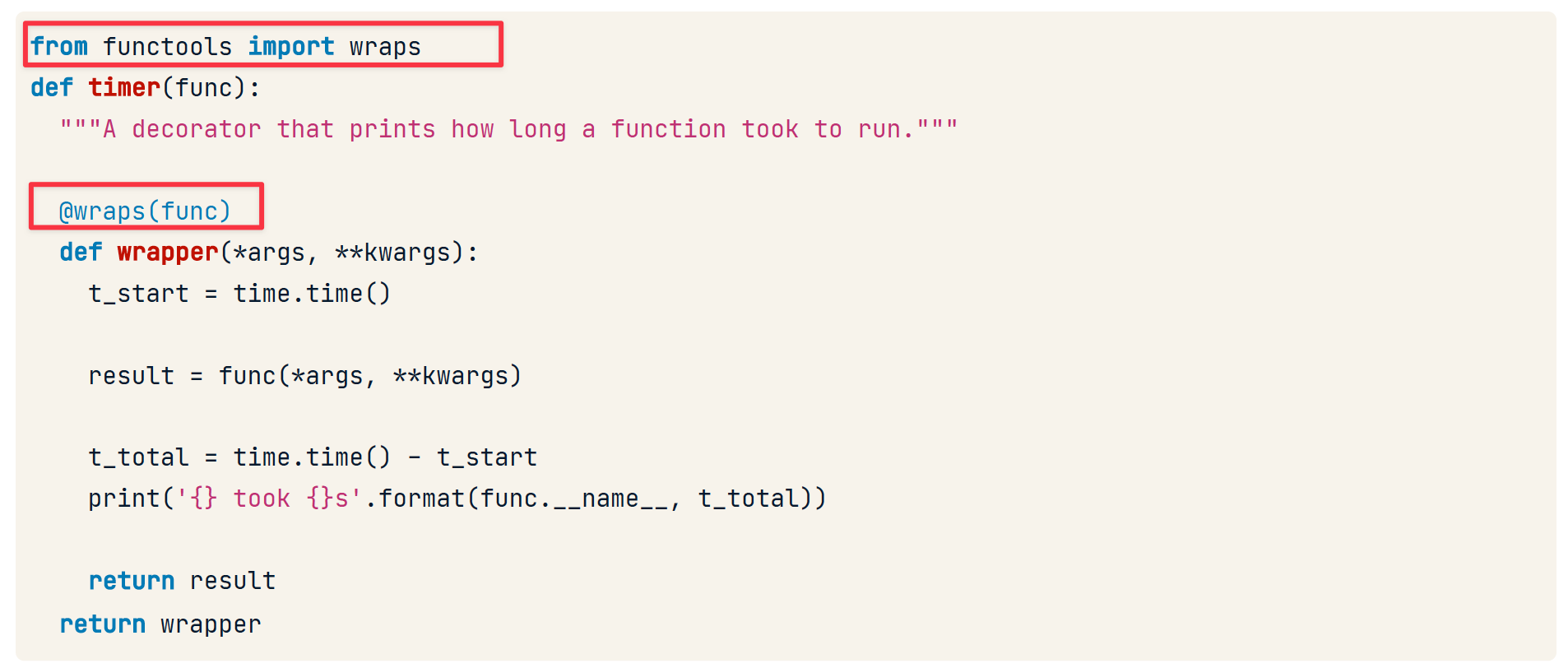

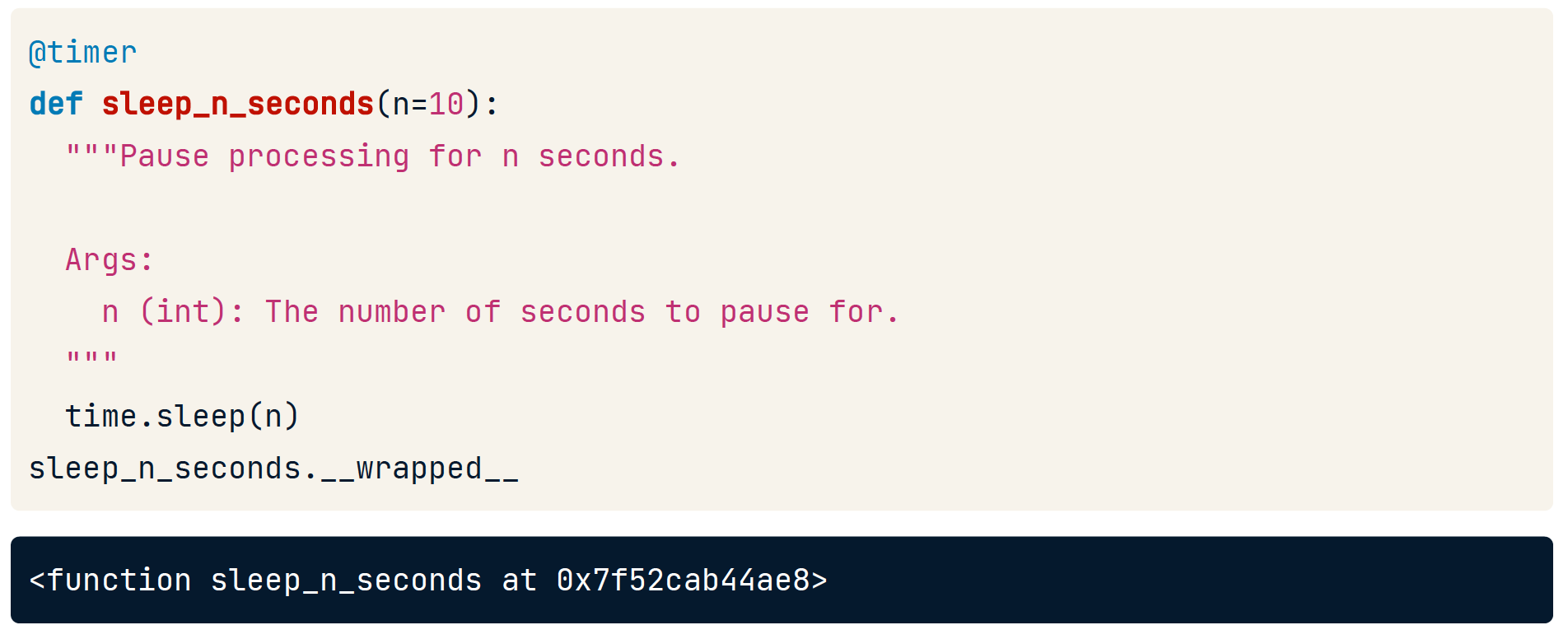

functools.wraps

由于被修饰后,原有的metadata将被包装而无法访问。

__name__:函数的名称__defaults__:函数的默认参数__doc__:函数的注释

给子函数wrapper添加修饰器即可解决这个问题。这样新函数的所有metadata将会赋值包装前函数的元数据。

此外,加上这个修饰器后支持访问包装前的函数。使用 __wrapped__

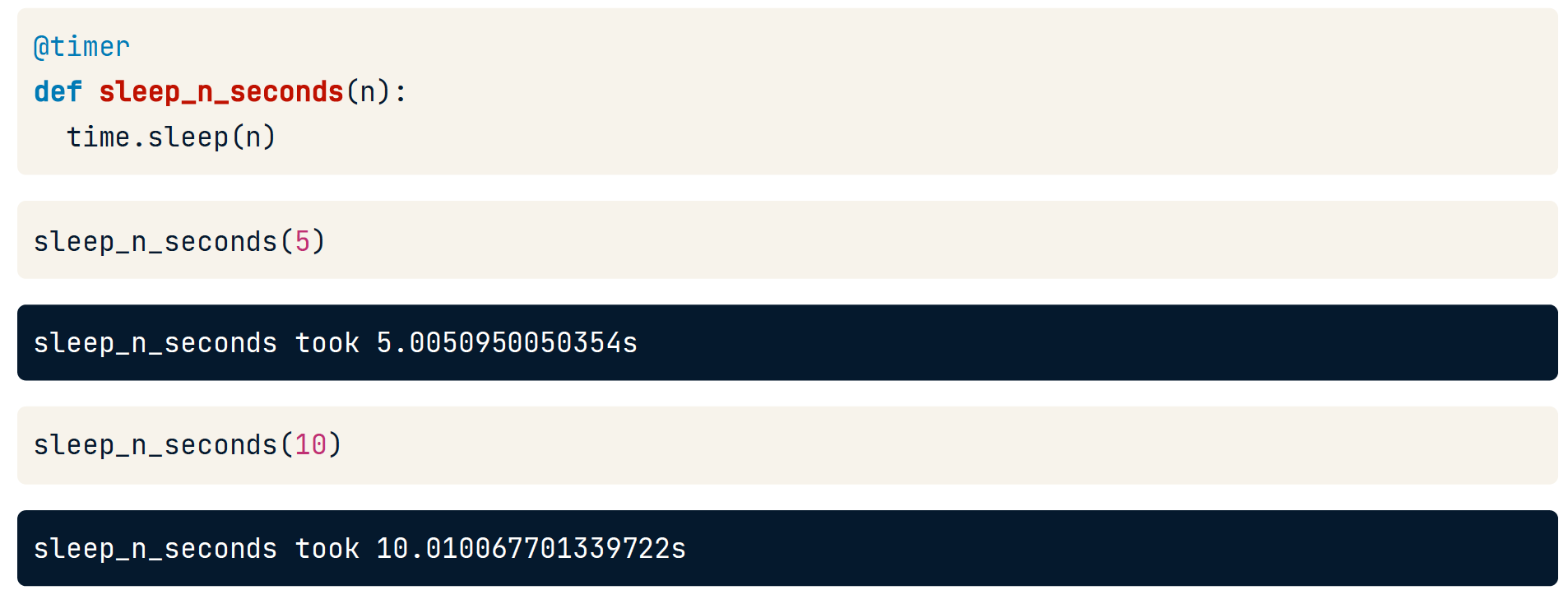

Decorators Application

@timer

import time

def timer(func):

"""A decorator that prints how long a function took to run."""

# Define the wrapper function to return.

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

# When wrapper() is called, get the current time.

t_start = time.time()

# Call the decorated function and store the result.

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

# Get the total time it took to run, and print it.

t_total = time.time() - t_start

print('{} took {}s'.format(func.__name__, t_total))

return result

return wrapper

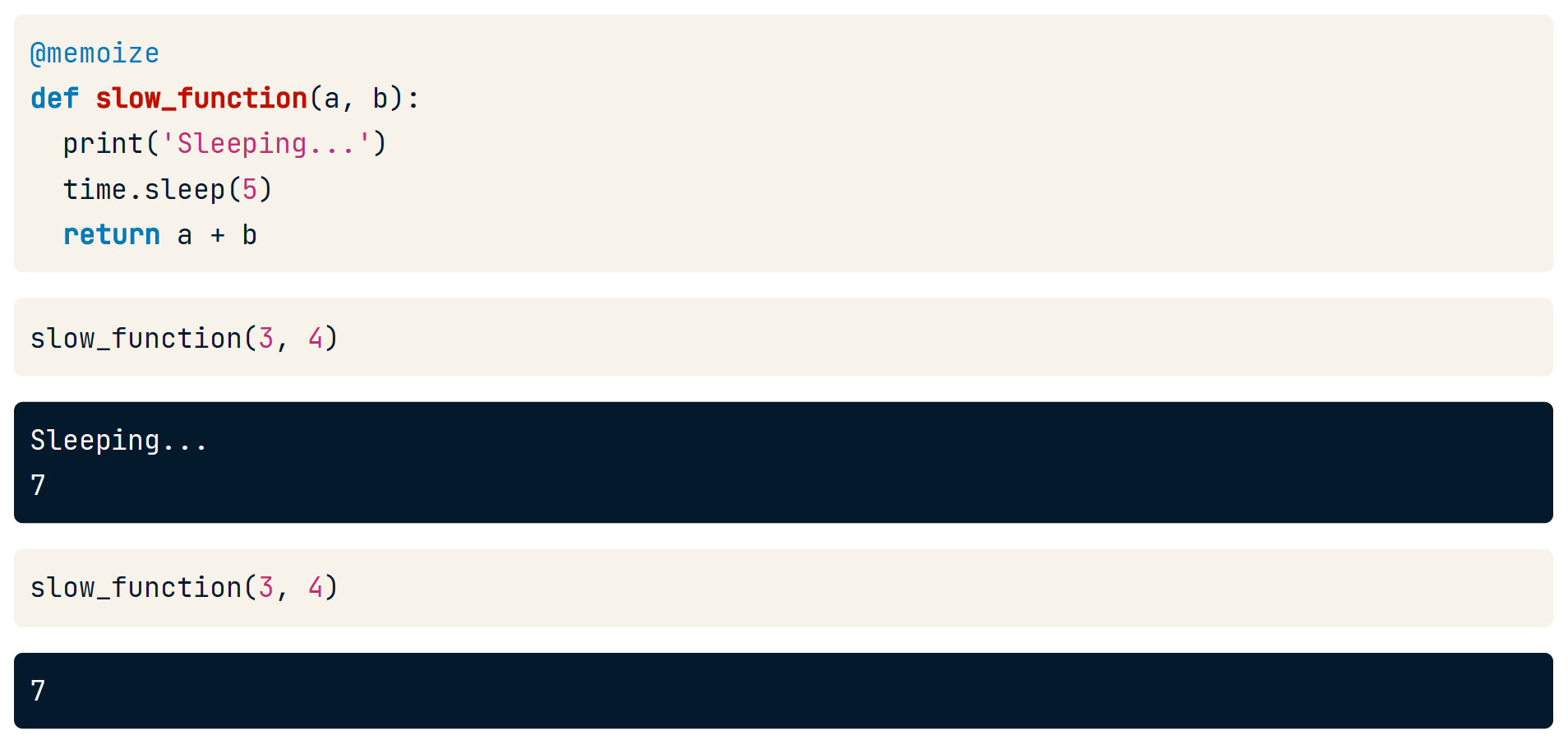

@memoize

def memoize(func):

"""Store the results of the decorated function for fast lookup

"""

# Store results in a dict that maps arguments to results

cache = {}

# Define the wrapper function to return.

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

# If these arguments haven't been seen before,

if (args, kwargs) not in cache:

# Call func() and store the result.

cache[(args, kwargs)] = func(*args, **kwargs)

# 注意如果cache中存在,则直接跳过了中间步骤而直接return

return cache[(args, kwargs)]

return wrapper

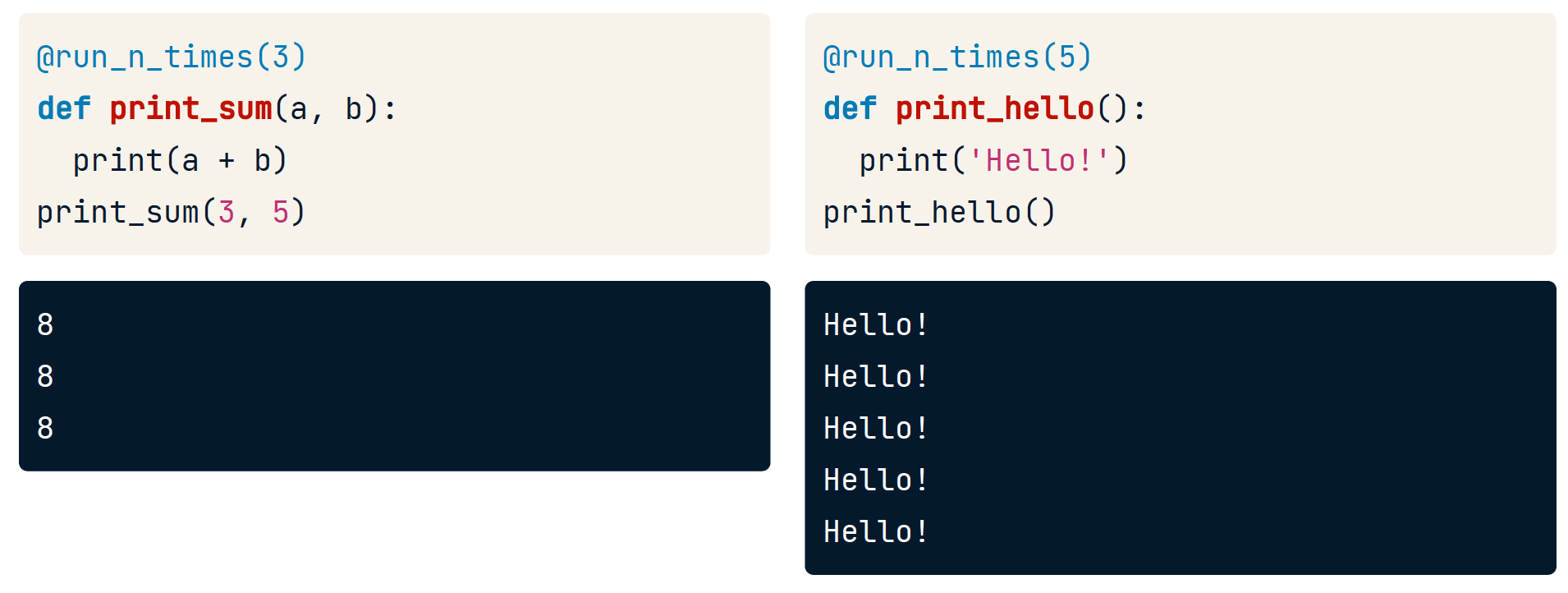

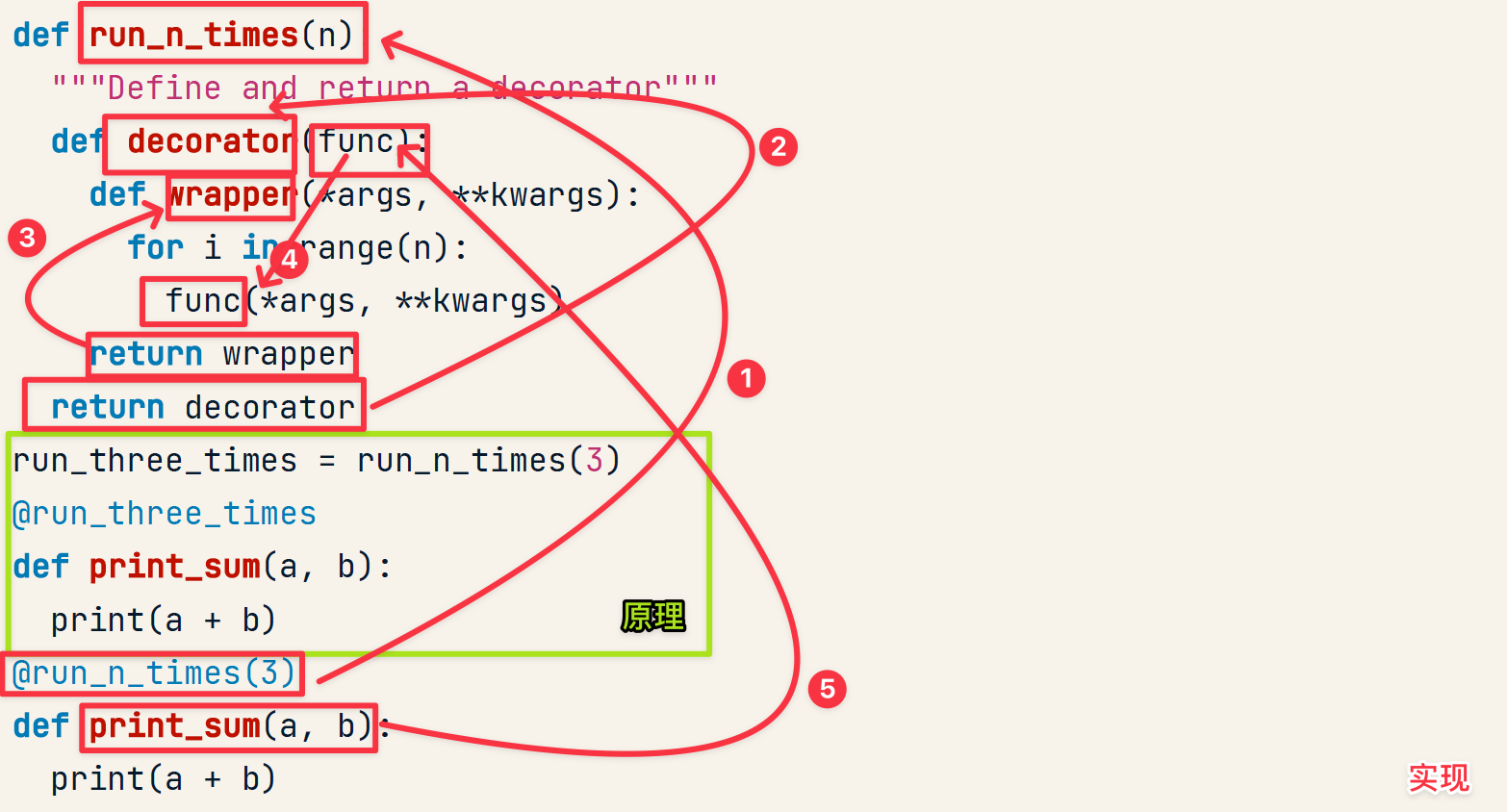

Decorators with args

run_n_times()

实现

不妨当做对旧的函数进行两次包装...

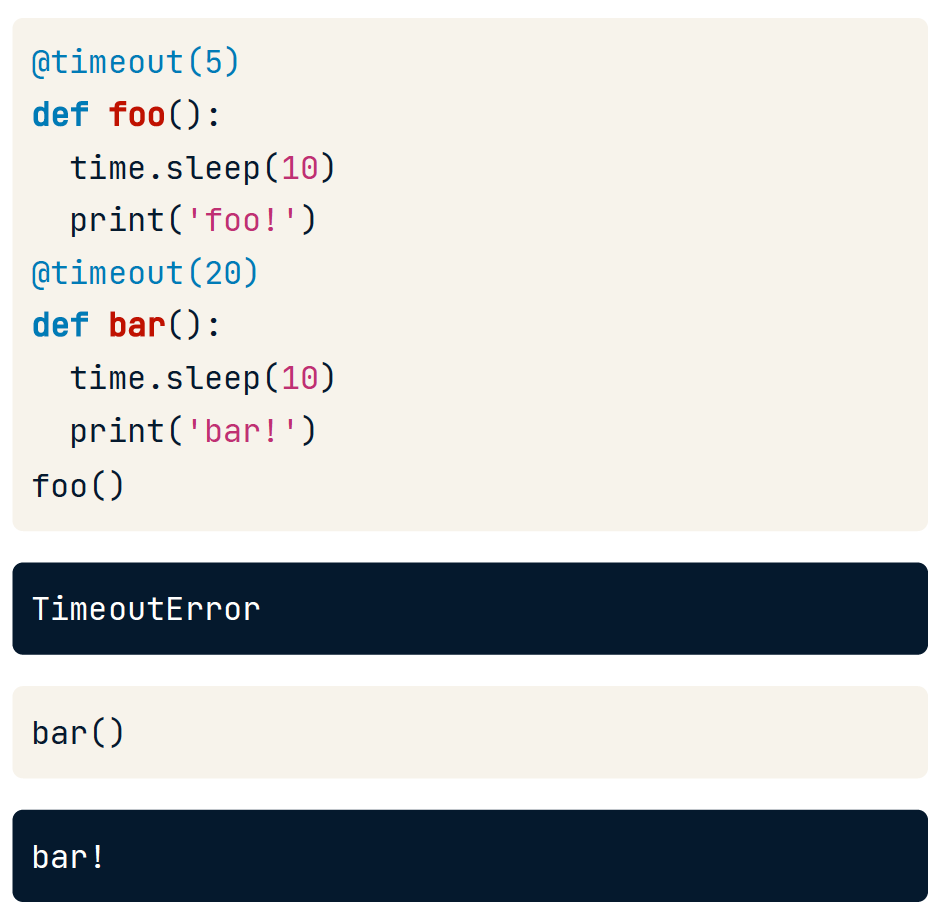

@timeout()

def timeout(n_seconds):

def decorator(func):

@wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

# Set an alarm for n seconds

signal.alarm(n_seconds)

try:

# Call the decorated func

return func(*args, **kwargs)

finally:

# Cancel alarm

signal.alarm(0)

return wrapper

return decorator

@tag(*tags)

给某物打标签意味着你给该物打了一个或多个字符串,作为标签。例如,我们经常给电子邮件或照片打上标签,这样我们以后就可以搜索它们了。你决定写一个装饰器,让你用一个任意的标签列表来标记你的函数。你可以将这些标签用于许多事情。

def tag(*tags):

# Define a new decorator, named "decorator", to return

def decorator(func):

# Ensure the decorated function keeps its metadata

@wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

# Call the function being decorated and return the result

return func(*args, **kwargs)

wrapper.tags = tags

return wrapper

# Return the new decorator

return decorator

@tag('test', 'this is a tag')

def foo():

pass

print(foo.tags)

('test', 'this is a tag')

@returns()

def returns(return_type):

# Complete the returns() decorator

def decorator(func):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

assert type(result) == return_type

return result

return wrapper

return decorator

@returns(dict)

def foo(value):

return value

try:

print(foo([1,2,3]))

except AssertionError:

print('foo() did not return a dict!')

foo() did not return a dict!